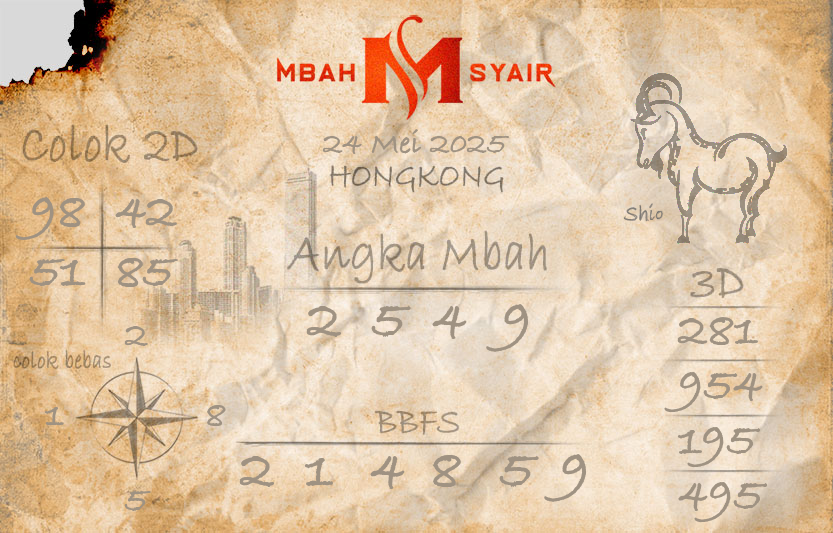

Prediksi hongkong sebagaimana dikenal menjadi prediksi hk terbaik, masih mencari Prediksi hk terpercaya tentu saja bukanlah hal yang bergitu sulit. Pada umumnya Prediksi hk terbaik ini sudah bekerja sama dengan agen besar hongkong yang dimana prediksi ini sudah dikeluarkan dengan berbentuk tabel, kenapa berbentuk tabel? Karna agen besar hongkong ingin memberikan para pemain semakin mudah menebak angka yang akan mereka tebak dan yang akan di pasang dihari berikutnya.

Tetapi lambat laun perubahan zaman membuat para permain semakin mudah untuk melakukan prediksi yang akan mereka pasang di kemudian harinya karena apa kami dari agen besar sudah membuat semakin memudahkan untuk pemain menebak angka yang mereka ingin pasang di pasaran hongkong ini.

Demi terciptanya kenyamanan serta kepercayaan para pemain tentu saja kami agen resmi Prediksi hk ini menjadi faktor sangat penting untuk prioritas para pemain agar merasakan kenyamanan. Baiklah rasanya sudah cukup sampai di sini pembahasan kita mengenal prediksi Prediksi hk hari ini yang bisa kami sampaikan kepada anda pastikan untuk anda selalu mengunjungi website kami agar mendapatkan info terbaru mengenai kode Prediksi hk yang akan datang.